7 Issues to Consider When Evaluating FoundationDB

FoundationDB enjoys a unique spot in the transactional NoSQL space given its positioning as a basic key-value database that can be used to build new, more application-friendly databases. Given that many of the guarantees provided by its core engine (such as multi-shard ACID transactions and high fault tolerance) are similar to those provided by the YugabyteDB database, our users often ask us for a comparison. These users are essentially trying to understand whether they should build their app directly using one of the three YugabyteDB APIs or should they explore/build a new database layer on FoundationDB first. This post is a first attempt at looking under the hood of FoundationDB to understand its strengths and weaknesses.

Introduction

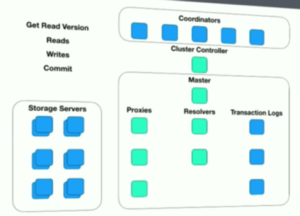

Started originally in 2009 as a proprietary database product, FoundationDB was one of the earliest attempts at adding ACID transactions to NoSQL databases. The company raised $22M in venture capital and had a v1.0 release in August 2013. However, it could gain only a couple major customers (Snowflake Computing and Wavefront) before getting acquired by Apple in March 2015. Since Apple had made the acquisition to restrict FoundationDB’s use to internal projects only, FoundationDB was taken off the market altogether. Fast forward to April 2018 when Apple open sourced FoundationDB under the Apache 2 license. The database had continued its evolution inside Apple from v3.0 (when it was acquired) to v5.0 (when it was open sourced). The latest major version is v6.0, released November 2018. It’s current high-level architecture is described here as well as shown in the figure below.

FoundationDB Architecture (Source: Video)

Fit for Internet-Scale Transactional Workloads?

Internet-scale transactional workloads are optimized for scale and performance without any compromises to data correctness. They require high read/write throughput with low latencies and topology-aware operations (such as multi-region active/active or reading from the nearest data center). In fact, Werner Vogels, Amazon.com CTO, notes that 70 percent of database requests at Amazon.com were key-value lookups, where only a primary key was used and a single row was returned. Examples include audit trail, stock market data, shopping cart checkouts, messaging applications and a user’s order history. Joins are typically done in the application tier, or using a framework such as Apache Spark or Presto to prevent inefficient queries in the serving tier. Essentially, the focus is on blazing-fast and correct single-key access patterns as the majority case.

From a 10000 ft level, FoundationDB looks like a great fit for such workloads. However, as is often the case, the truth is in the details. Let’s review how FoundationDB fares in practice. Before we dive into the details, a quick note about FoundationDB official documentation. This documentation does a poor job of explaining how the basic internal functions of the database (such as sharding and replication) work. As a result, learning these basics becomes an onerous exercise that involves reading documentation followed by watching videos and reviewing forums posts.

1. Data Modeling

Developer agility is directly correlated to how easily and efficiently the application’s schema and query needs can be modeled in the database of choice. FoundationDB offers multiple options for this problem.

Key Value

At the core, FoundationDB provides a custom key-value API. One of the most important properties of this API is that it preserves dictionary ordering of the keys. The end result is efficient retrieval of a range of keys. However, the keys and value are always byte strings. This means that all other application-level data types (such as integers, floats, arrays, dates, timestamps etc.) cannot be directly represented in the API and hence have to be modeled with specific encoding and serialization. This can be an extremely burdensome exercise for developers. FoundationDB tries to alleviate this problem by providing a Tuple Layer, that encodes tuples like (state, country) into keys so that reads can simply use the prefix (state,). The key-value API also has support for strongly consistent secondary indexes as long as the developer manually does the work of updating the secondary index explicitly as part of the original transaction (that updates the value of the primary key). The TL;DR here is that FoundationDB’s key-value API is not really meant for developing applications directly. It has the raw ingredients that can be mixed in various ways to create the data structures that can then be used to code application logic.

FoundationDB’s approach highlighted above is in stark contrast to YugabyteDB’s approach of providing three application-friendly APIs right out of the box. The simplest one is YEDIS, a transactional key-value API that is also wire compatible with Redis commands and client drivers. Rich single-key-access-optimized data structures such as hashmaps, sets, sorted sets, publish/subscribe channels, time series are natively built-in to the API. End result is that developers spend more time writing application logic rather than building database infrastructure. And, developers needing multi-key transactions and strongly consistent secondary indexes can chose YugabyteDB’s flexible schema YCQL API or the relational YSQL API.

Document

A MongoDB 3.0-compatible Document Layer was released in the recent v6.0 release of FoundationDB. As with any other FoundationDB Layer, the Document Layer is a stateless API that internally is built on top of the same core FoundationDB key-value API we discussed earlier. The publicly stated intent here is to solve two of most vexing problems faced by MongoDB deployments: seamless horizontal write scaling and fault tolerance with zero data loss. However, the increase in application deployment complexity can be significant. Every application instance now has to either run a Document Layer instance as a sidecar on the same host or all application instances connect to a Document Layer service through an external Load Balancer. Note that strong consistency and transactions are disabled in the latter mode which means this mode is essentially unfit for transactional workloads.

MongoDB v3.0 was released March 2015 (v4.0 from June 2018 is the latest major release). Given that the MongoDB API compatibility is 4 years old, this Document Layer would not be taken be seriously in the MongoDB community. And given the increase in deployment complexity, even non-MongoDB users needing a document database will think twice. In contrast, YCQL, YugabyteDB’s Cassandra-compatible flexible-schema API, has none of this complexity and is a superior choice to modeling document-based internet-scale transactional workloads. It provides a native JSONB column type (similar to PostgreSQL), globally consistent secondary indexes, as well as, multi-shard transactions.

Relational

FoundationDB does not yet offer a SQL-compatible relational layer. The closest it has is the record-oriented Record Layer. The goal is to help developers manage structured records with strongly-typed columns, schema changes, built-in secondary indexes, and declarative query execution. Other than the automatic secondary index management, there are no relational data modeling constructs such as JOINs and foreign keys available. Also note that records are instances of Protobuf messages that have to be created/managed explicitly as opposed to using a higher level ORM framework common with relational databases.

Instead of exposing a rudimentary record layer with no explicit relational data modeling, YugabyteDB takes a more direct approach to solving the need for distributed SQL. It’s YSQL API not only supports all critical SQL constructs but also is fully compatible with the PostgreSQL language. In fact, it reuses the stateless layer of the PostgreSQL code and changes the underlying storage engine to DocDB, YugabyteDB’s distributed document store common to all the APIs.

2. Fault Tolerance

Distributed databases achieve fault tolerance by replicating data into enough independent failure domains so that loss of one domain does not result is data unavailability and/or loss. Based on a recent presentation, we can infer that replication in FoundationDB is handled at the shard level similar to YugabyteDB. In Replication Factor 3 mode, every shard has 3 replicas distributed across the available storage servers in such a way that no two storage servers have the same replicas.

As we have previously highlighted in “How Does Consensus-Based Replication Work in Distributed Databases?”, a strongly consistent database standardizing on Raft (a more understandable offshoot of Paxos) for data replication makes it easy for users to reason about the state of the database in the single key context. FoundationDB takes a very different approach in this regard. Instead of using a distributed consensus protocol for data replication, it follows a custom leaderless replication protocol that commits writes to ALL replicas (aka the transaction logs) before the client is acknowledged.

FoundationDB’s Custom Leaderless Replication Protocol (Source: Video)

Write Unavailability

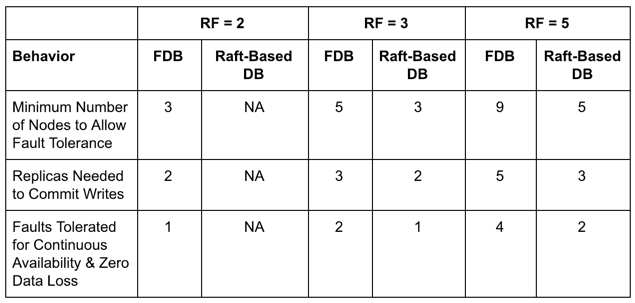

Let’s compare the behavior of FoundationDB and a Raft-based DB such as YugabyteDB in the context of RF=2, 3 and 5. Note that while RF=2 is allowed in FoundationDB, it is disallowed in Raft-based DBs since it is not a fault-tolerant configuration.

Replication in FoundationDB vs. Raft-based DB

Replication in FoundationDB vs. Raft-based DB

The above table shows that FoundationDB’s RF=2 is equivalent to Raft’s RF=3 and FoundationDB’s RF=3 is equivalent to Raft’s RF=5. While it may seem that FoundationDB and a Raft-based DB behave similarly under failure conditions, that is not the case in practice. In a 3-node cluster with RF=2, FoundationDB has 2 replicas of any given shard on only 2 of the 3 nodes. If the 1 node not hosting the replica dies then writes are not impacted. If any of the 2 nodes hosting a replica die, then FoundationDB has to rebuild the replica’s transaction log on the free node first before writes are allowed back on for that shard. So the probability of writes being impacted for a single shard because of faults is 2/3 i.e. RF/NumNodes.

In a 3-node RF=3 Raft-based DB cluster, there are 3 replicas (1 leader and 2 followers) on 3 nodes. Failure of the node hosting a follower replica has no effect on writes. Failure of the node hosting the leader simply leads to leader election among the 2 remaining follower replicas before writes are allowed back on that shard. In this case, the probability of writes being impacted 1/3, which is half of FoundationDB’s. Note that the probability here is essentially 1/NumNodes.

Leader-driven replication ensures that the probability of write unavailability in a Raft-based DB is at least half of that of FoundationDB’s. Also, higher RFs in FoundationDB increase this probability while it is independent of RF altogether in a Raft-based DB. Given that failures are more common in public cloud and containerized environments, the increased probability of write unavailability in FoundationDB becomes a significant concern to application architects.

Recovery Time After Failure

The second aspect to consider is recovery times after failure in the two designs. This recovery time directly impacts the write latency under failure conditions. We do not know how long FoundationDB would take to rebuild the transaction log of a shard at a new node compared to the leader election time in Raft. However, we can assume that Raft’s leader election (being simply a state change on a replica) would be a faster operation than the rebuilding of a FoundationDB transaction log (from other copies in the system).

3. ACID Transactions

FoundationDB provides ACID transactions with serializable isolation using optimistic concurrency for writes and multi-version concurrency control (MVCC) for reads. Reads and writes are not blocked by other readers or writers. Instead, conflicting transactions fail at commit time and have to be retried by the client. Since the transaction logs and storage servers maintain conflict information for only 5 seconds and entirely in memory, so any long-running transaction exceeding 5 seconds will be forced to abort. Another limitation is that any transaction can have a max of 10MB of affected data.

Again, the approach above is significantly different than that of YugabyteDB. As described in “Yes We Can! Distributed ACID Transactions with High Performance”, YugabyteDB has a clear distinction between blazing-fast single-key & single-shard transactions (that are handled by a single Raft leader without involving 2-Phase Commit) and absolutely-correct multi-shard transactions (that necessitate a 2-Phase Commit across multiple Raft leaders). For multi-shard transactions, YugabyteDB uses a special Transaction Status system table to track the keys impacted and the current status of the overall transaction. Not only this tracking allows serving reads and writes with fewer application-level retries, it also ensures that there is no artificial limit on the transaction time. As a SQL-compatible database that needs to support client-initiated “Session” transactions both from the command line and from ORM frameworks, ignoring long-running transactions is simply not an option for YugabyteDB. Additionally, YugabyteDB’s design obviates the need for any artificial transaction data size limits.

4. High-Performance Storage Engine

FoundationDB’s on-disk storage engine is based on SQLite B-Tree and is optimized for SSDs. This engine has multiple limitations including high latency for write-heavy workloads as well as for workloads with large key-values (because B-Trees store full key-value pairs). Additionally, range reads seek more versions than necessary resulting in higher latency. Lack of compression also leads to high disk usage.

Given its ability to serve data off SSDs fast and that too with compression enabled, Facebook’s RocksDB LSM storage engine is increasingly becoming the standard among modern databases. For example, YugabyteDB’s DocDB document store uses a customized version of RocksDB optimized for large datasets with complex data types. However, as described in this presentation, FoundationDB is moving towards Redwood, a custom prefix-compressed B+Tree storage engine. The expected benefits are longer read-only transactions, faster read/write operations and smaller on-disk size. The issues concerning write-heavy workloads with large key-value pairs will remain unresolved.

5. Multi-Region Active/Active Clusters

A globally consistent cluster can be thought of as a multi-region active/active cluster that allows writes and reads to be taken in all regions with zero data loss and automatic region failover. Such clusters are not practically possible in FoundationDB because the commit version for every transaction is handed out by a single process (called Master) running in only one of the regions. For a truly random and globally-distributed OLTP workload, majority of transactions will be outside the region where the single Master resides and hence will pay the cross-region latency penalty. In other words, FoundationDB writes are practically single-region only as it stands today.

Instead of global consistency, Multi-DC mode in FoundationDB focuses on performing fast failover to a new region in case the master region fails. Two options are available in this mode. First is the use of asynchronous replication to create a standby set of nodes in a different region. The standby region can be promoted to the master region in case the original master region fails altogether. Some recently committed data may be lost in this option. The second option is to augment the first option with the use synchronous replication of the mutation log to the standby region. The advantage here is that the mutation log will allow access to recently committed data even in the standby region in case the master region fails.

6. Kubernetes Deployments

A well-documented and reproducible Kubernetes deployment for FoundationDB is officially still a work-in-progress. One of the key blockers for such a deployment is the inability to specify hosts using hostname as opposed to IP. Kubernetes StatefulSets create ordinal and stable network IDs for their pods making the IDs similar to hostnames in the traditional world. Using IPs to identify such pods would be impossible since those IPs would change frequently. The latest thread on the design challenges involved can be tracked in this forum post.

As a multi-model database providing decentralized data services to power many microservices, YugabyteDB was built to handle the ephemeral nature of containerized infrastructure. A Kubernetes YAML (with definitions for StatefulSets and other relevant services) as well as a Helm Chart are available for Kubernetes deployments.

7. Ease of Use

Last but not least, we evaluate the ease of use of a distributed system such as FoundationDB.

Architectural Simplicity

Easy to understand systems are also easy to use. Unfortunately, as previously highlighted, FoundationDB is not easy to understand from an architecture standpoint. A recent presentation shows that the read/write path is extremely complex involving storage servers, master, proxies, resolvers and transaction logs. The last four are known as the write-subsystem and treated as a single unit as far as restarts after failures are concerned. However, the exact runtime dependency between these four components is difficult to understand.

Compare that with YugabyteDB’s system architecture involving simply two components/processes. YB-TServer is the data server while YB-Master is the metadata server that’s not present in the data read/write path (similar to the Coordinators in FoundationDB). The Replication Factor of the cluster determines how many copies of each shard should be placed on the available YB-TServers (the number of YB-Masters always equals the Replication Factor). Fault tolerance is handled at the shard level through per-shard distributed consensus, which means loss of YB-TServer impacts only a small subset of all shards who had their leaders on that TServer. Remaining replicas at the available TServers auto-elect new leaders using Raft in a few seconds and the cluster is now back to taking writes for the shards whose leaders were lost. Scaling is handled by simply adding or removing YB-TServers.

Local Testing

FoundationDB local macOS package is a single node deployment with no ability to test foundational database features such as horizontal scaling, fault tolerance, tunable reads and sharding/rebalancing. Even the official FoundationDB docker image has no instructions. The only way to test the core engine features is to do a multi-machine Linux deployment.

YugabyteDB can installed a local laptop using macOS/Linux binaries as well as Docker and Kubernetes (Minikube). This local cluster setup can then be used to not only test API layer features but also core engine features described earlier.

Command Line Shell

fdbcli is FoundationDB’s command line shell that gets auto-installed along with the FoundationDB server. It connects to the appropriate FoundationDB processes to provide status about the cluster. One significant area of weakness is the inability to easily introspect/browse the current data managed by the cluster. For example, when using the Tuple Layer (which is very common), FoundationDB changes the byte representation of the key that gets finally stored. As highlighted in this forum post, unless the exact tuple encoded key is passed as input, fdbcli will not show any data for the key.

Instead of creating a new command line shell, YugabyteDB relies on the command line shells of the APIs it is compatible with. This means using redis-cli for interacting with the YEDIS API, cqlsh for interacting with the YCQL API and psql for interacting with the YSQL API. Each of these shells are functionally rich and support easy introspection of metadata as well as the data stored.

Summary

The single most important function of a database is to make application development and deployment easier. FoundationDB misses the mark on this function. On one hand, the API layer is aimed at giving flexibility to systems engineers as opposed to solving real-world data modeling challenges of application developers. On the other hand, the core engine seemingly favors the approaches highlighted in architecturally-limiting database designs such as Yale’s Calvin (2012) and Google’s Percolator (2010). It is also reinventing the wheel when it comes to high-performance storage engines.

As previously highlighted, we at YugaByte believe that both Calvin (for distributed transaction processing with global consensus) and Percolator (for commit version allocation by a single process) are architecturally unfit for random access workloads on today’s truly global multi-cloud infrastructure. Hence, our bias towards the Google Spanner (2012) design for globally distributed transaction processing using partitioned consensus and 2PC. The most important benefit of this design is that no single component can become a performance or availability bottleneck especially in a multi-region cluster. YugabyteDB also leverages this decade’s two other popular database technology innovations – Stanford’s Raft (2013) for distributed consensus implementation and Facebook’s RocksDB (2012) for fast key-value LSM-based storage.

Assuming the FoundationDB’s API layer will get strengthened with introduction of new Layers, the core engine limitations can live forever. This will hamper adoption significantly in the context of internet-scale transactional workloads where each individual limitation gets magnified and becomes critical in its own right.

What’s Next?

- Compare YugabyteDB in depth to databases like CockroachDB, Google Cloud Spanner and Amazon DynamoDB.

- Get started with YugabyteDB on macOS, Linux, Docker and Kubernetes.

- Contact us to learn more about licensing, pricing or to schedule a technical overview.